Compound Interest, Part 4: The Hidden Opportunity Cost Of Debt

Photo by Kdsphotos, CC0 1.0 license

This is the fourth installment of a 5-part series examining the massive impact compound interest can have on your journey to financial freedom.

Previously in the series we introduced the phenomenon of compound interest, explored how it can serve as a rocket to riches capable of powering us through the millionaire barrier, and discovered how it can serve as the best double agent the world has ever seen.

By now you should be familiar with how to calculate the total amount of interest incurred over the life of a loan when you purchase something on credit, whether that be in the form of a credit card, auto loan, student loan, or a mortgage.

Adding interest costs to the original loan amount is a much more accurate method of determining the total cost of a purchase than is considering just the loan amount itself. Yet correctly calculating the TRUE cost of debt requires one final piece of the compound interest puzzle, which we haven’t yet addressed.

Today we’re taking a look at how compound interest creates a well-camouflaged, deadly cost of debt which has an outsized impact on your ability to escape the rat race and obtain financial freedom. This secret exists in the form of opportunity cost.

What Is Opportunity Cost?

Opportunity cost consists of the value one gives up in order to pursue an alternative course of action. Uhh… say what? Let’s try that again, in English this time.

Let’s say you’re an hourly employee who comes down with the flu, but you’ve already used up all of your vacation and sick days for the year. You can call in sick, but you won’t be paid if you do. Still, you feel absolutely terrible, so you make the decision to call in to your supervisor to let them know you’re ill and won’t be in for the day.

The opportunity cost of calling in sick in this scenario consists of two amounts:

- The wages you would have otherwise earned had you dragged yourself in to work.

- The future money you could have made with those wages had you invested them.

You gave up both the current value of those lost wages AND their future earning potential in order to pursue an alternative course of action (rest).

Loan Interest – The Predator You Can See

Now that we’ve defined the concept of opportunity cost, let’s explore how compound interest contributes to an additional, hidden cost of debt beyond simple loan interest.

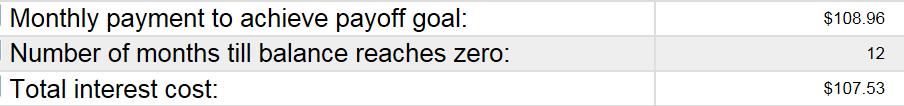

Consider a scenario where you purchase a new, top-of-the-line TV for $1,200 using your credit card, which possesses the national average interest rate of 16.15%. You set a goal of paying off this balance in 12 months, which our familiar credit card payoff calculator tells us will require monthly payments of $108.96:

You diligently make these payments and pay off the TV a year later, paying $107.53 in interest on the balance along the way.

The average person would believe they purchased a TV for $1,200, but by now you know better. You factor in the effects of compound interest on the purchase and know that your TV cost a total of $1,307.53 ($1,200 + $107.53), 9% more than the original purchase price.

But don’t rest on your laurels just yet, because we still haven’t calculated the full cost of your new TV. What’s missing? You guessed it – we still have to factor in what else you could have done with the $107.53 which you paid in credit card interest.

The Stealthy Second Element of Opportunity Cost

After reading part 2 of this series, you’re now well aware of the power that compound interest has to grow exponentially over time in a savings or investment account.

So let’s assume that if you hadn’t been losing a portion of each credit card payment to compound interest, you would have taken that same amount and invested it instead at the same time that you made your credit card payment every month.

The opportunity cost of your TV purchase consists in part of the money you would have otherwise earned via compound interest had you saved or invested the cash that you were instead losing by way of compound interest on your credit card balance.

Foregone Future Value – A Seldom Seen Danger

Calculating this amount would be a quite monotonous and time-consuming exercise involving the use of multiple online calculator types were it not for the existence of this handy cost of debt calculator, which does all of the heavy lifting for us.

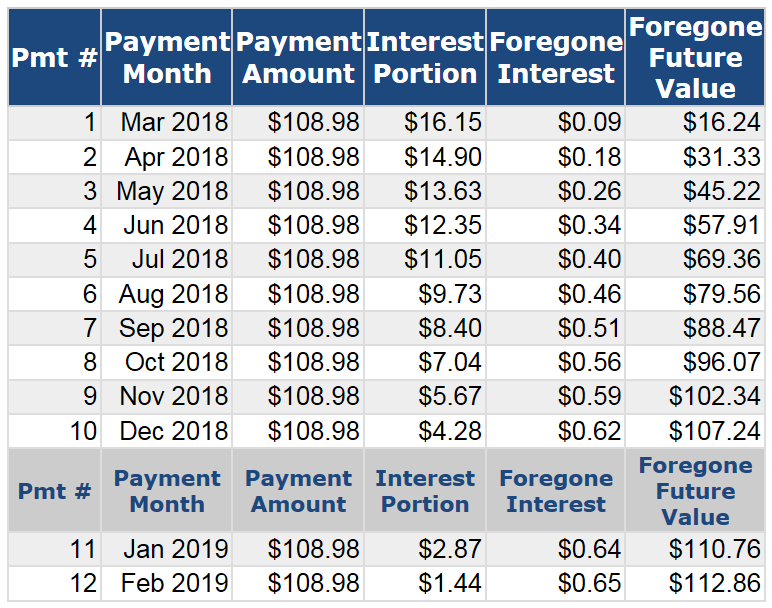

Plugging in our credit card balance, rate, and payment info from our TV purchase above (use monthly payments of $108.975 rather than $108.96 to resolve a rounding discrepancy) and using the historical annual average of 7% for our hypothetical stock market investments returns the below results:

We see per the Foregone Future Value column above that had you instead invested the $107.87 which you paid in credit card interest, it would have grown to a total of $112.86 after one year. So you’re out not only the original $107.87 lost to credit card interest, but the chance to keep that money AND earn an additional $4.99 in interest ($112.86 future value – $107.87 starting balance).

The total opportunity cost of the debt you incurred by purchasing the TV on credit is therefore the $107.87 you lost to credit card interest, plus the $112.86 you could have had in the form of an investment account balance – $220.73.

This is 18.4% more than the original purchase price of the TV, a hard-to-spot and stealthy surcharge.

Mortgage Opportunity Cost – The Silent Killer

An 18.4% cost increase is bad any way you slice it, but it pales in comparison to what happens when we calculate the opportunity cost of even larger loans over longer periods of time after giving compound interest a longer timeframe with which to work.

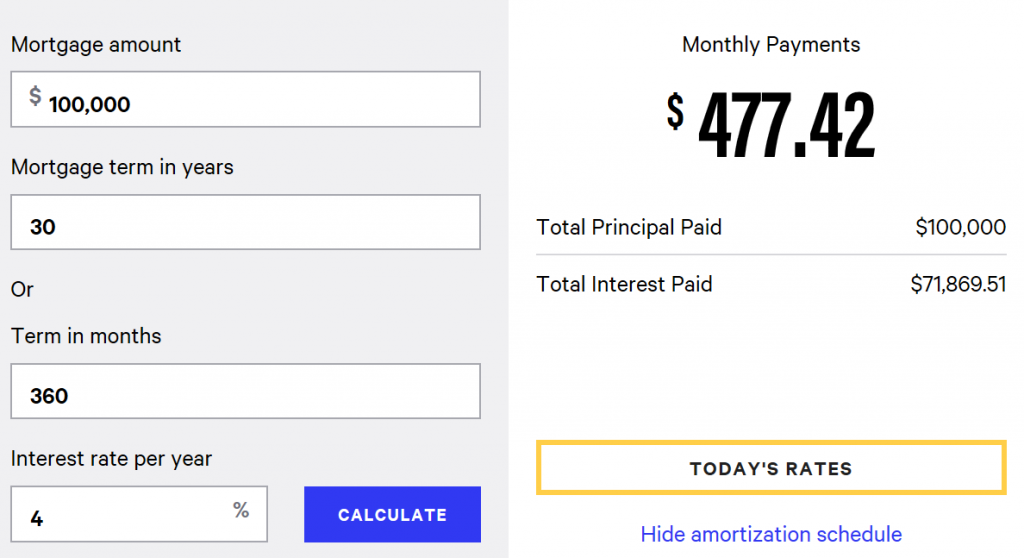

For example, let’s calculate the opportunity cost of paying 4% interest on a $100,000 mortgage in monthly payments spread over 30 years. Our mortgage loan amortization schedule calculator tells us that this will require monthly payments of $477.42 for 30 years and will result in a total of $71,869.51 in interest paid:

If that $71,869.51 of interest were not otherwise lining the pockets of our mortgage lender, we could have saved and invested it instead. The decision to forego this in favor of borrowing money to purchase this home represents the opportunity cost of this mortgage.

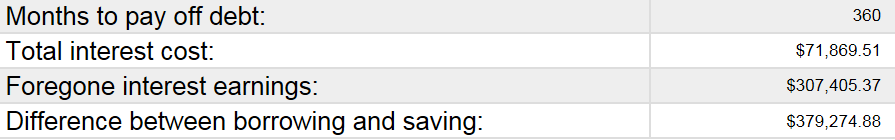

Plugging our loan information and a 7% rate of return on our hypothetical investments into our cost-of-debt calculator (enter monthly payment as $477.415299 to avoid rounding errors), we discover that if we had invested the money that we are otherwise losing to mortgage interest on a monthly basis, it would have grown to a total of $307,405.37 after 30 years:

This means that the cost of our mortgage in this scenario is far, far higher than the original $100,000 price tag considered by most. First, we have the $71,869.51 we’ve already signed away in the name of mortgage interest, a 71.9% increase over the original $100,000 loan.

Then we have the $307,405.37 we would have accumulated in our investment account thanks to contributions and compound interest growth over 30 years had we not signed that $71,869.51 away. This triples the original mortgage amount, a cost increase of 307.4%.

Adding the two together we find that the total opportunity cost of the mortgage is a mind-numbing $379,274.88, a 379.3% increase over the original $100,000 balance. This number represents the total cost of purchasing something which we could not afford outright and had to purchase on credit.

The Piercing Talons Of Debt Opportunity Cost

Projecting interest owed AND calculating the opportunity cost of that interest are essential to understanding the true cost of purchasing something on credit and falling into the clutches of debt.

In the above example, the couple considering the $100,000 mortgage may very well have made a different decision had they known the true price tag would amount to $479,274.88.

Informing your purchasing decisions with this information has the potential to dramatically change your long-term financial picture. Just one large-scale purchase avoided or modified can have an impact of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Identify The Hidden Costs Of Your Own Debt

Using what you’ve learned in this article and the below compound interest calculators, see if you can pick out the hidden opportunity costs of your own debt:

- Compound Interest Calculator – Use to calculate the growth of a starting balance over time at a given interest rate (select “View Report” for year-by-year details).

- Debt Payment Principal & Interest Calculator – Use to calculate what portion of a debt payment is applied to principal vs. interest based on loan balance and interest rate.

- Credit Card Payoff Calculator – Use to view credit card payoff timeline, total interest incurred, and principal vs. interest portions of payments.

- Mortgage Loan Amortization Schedule Calculator – Use to calculate the total interest owed over a given mortgage term, as well as the impact of making additional payments (select “show amortization schedule” for year-by-year details).

- Cost of Debt Calculator – Use to calculate the opportunity cost of debt payments in the form of the interest you could have otherwise earned with the money you are losing to interest payments on debt (scroll down to see payment-by-payment details).

Extra Bonus – Did you know that owls have three different eyelids? Or that the world’s smallest owl is only 5-6 inches tall? Brush up on your owl trivia here and here to impress your family and friends with both your financial and feathered wisdom.

Up Next – Compound Interest, Part 5: Benjamin Franklin’s 200-Year Experiment

I don’t know that the true cost of the mortgage includes the full opportunity cost of investing in the markets because you hade an appreciating asset (hopefully). You’d have take some of that appreciation off of the opportunity cost.

In any case, it is a good exercise for people to understand the total cost of the mortgage over its lifetime. That is in the closing documents but by that time it is too late.

I’d add that there is not only opportunity cost of missed investments but missed adventures, more time with family, more time for self development. Debt really takes a lot away from us and it’s best to rid yourself of it ASAP.

Thanks for the comment, Drew! You bring up a good point. While the $71,869.51 in mortgage interest from the above scenario will come off the top no matter what, the foregone future earnings portion of the mortgage opportunity cost would potentially be offset to some extent by the potential for home value to increase over time (though the opposite could also be true if the home loses value).

For sake of reference, the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price NSA Index shows national housing prices have increased by 13.2% over the last 10 years. The S&P 500 index indicates it has grown by 100.9% over that same span:

https://us.spindices.com/indices/real-estate/sp-corelogic-case-shiller-us-national-home-price-nsa-index

https://us.spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-500

The difference indicates that the foregone future earnings portion of the opportunity cost from the scenario in the article would potentially be 13.1% lower. But we can’t forget that mortgages also come with potentially expensive transaction costs that investments may not. For example, a recent ValuePenguin study found that the closing costs on the national average home value of $198,000 would total $7,227, or 3.65%:

https://www.valuepenguin.com/mortgages/average-closing-costs

Add this to other cost-of-home-ownership factors such as annual property taxes, home insurance, and required maintenance and you may well have Robert Kiyosaki’s argument in Rich Dad Poor Dad that your home shouldn’t be considered an investment at all:

http://www.richdad.com/Resources/Rich-Dad-Financial-Education-Blog/December-2017/the-financial-statement-foundation-for-being-rich.aspx

But that’s another discussion for another day. While you’re correct that the total cost of a mortgage is disclosed within closing documents, in my experience the total listed consists only of principal + total interest per the loan’s amortization schedule. I’ve personally never seen a transaction which included the foregone future earnings portion of opportunity cost in that calculation as well, though it should.

I agree with you whole-heartedly regarding debt coming with intangible opportunity costs in addition to the tangible costs. A lack of financial freedom due to debt prevents far too many people from being able to live the life they desire. Thanks for weighing in!

I would say the biggest flaw in this argument (albeit a good one, thank you), is you are neglecting to account for the individual “needing” that item to begin with. So if we run around saving all of our money all the time we could become quite rich but would not have clothes on our back or a roof over our head.

This argument is sound with frivolous purchases, but one may argue at some point you will want SOME kind of TV, and live SOMEwhere. So regardless of the cost and interest, through that period if you didn’t buy that house, you could be renting and paying more than the cost of the house plus interest. That gives you another opportunity cost consideration, on whether you rent or take a loan out for a house.

But that wouldn’t make your point, and your point was a good one.

Thanks! Great Article!

Thanks for the kind words! I completely agree with your premise regarding the fact that some purchases and expenses are inevitable as we live our daily lives. We can’t simply save every penny that we earn. We all need to purchase necessary items like food and housing, to name just a few.

But there’s an important distinction to be made here. While there’s definitely an “opportunity cost” of ANY purchase or expense in terms of the foregone future value of the money used to make a purchase, that’s not the focus of this article.

This post is intended to address specifically the opportunity cost of DEBT, in the context of this 5-part series detailing how compound interest can work both for and against you.

My message is not to avoid purchasing a television or a home. It’s not even to avoid taking out loans or accumulating debt to do so. My intent in writing this article was simply to enable others to properly evaluate the TRUE price tag of purchasing something on credit so they can make an informed purchasing decision.

Purchasing something you can’t afford outright allows the power of compound interest to work against you in three separate ways:

1) The penalty you’ll pay in terms of loan interest on your purchase

2) Your foregone future earnings had you invested the money used to make the purchase

3) The foregone future earnings had you invested the money you are losing to loan interest

You are absolutely right that opportunity cost factors heavily into the rent-vs.-buy decision, which will vary based on each individual situation. If rent is greater than the principal + total interest over the amortization schedule of a mortgage, the opportunity cost of owning may be less than that of rent. Though other factors such as closing costs, property taxes, insurance, and ongoing maintenance have to be factored in as well.

In our case, renting was significantly cheaper than was purchasing our own home, but we also had a dream of homeownership. We managed to dodge the opportunity cost bullet by reverse-engineering our home shopping budget from our desired payoff timeline (3 years).

If interested, you can read more about our journey to homeownership at the below two links. Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

https://www.thefinancialfreedomproject.com/about/

https://www.thefinancialfreedomproject.com/financial-intentionality-the-9th-wonder-of-the-world/

Awesome explanation my friend.

I just signed up and look forward to the future posts in the series. I love the concept of being able to put that money to work, instead of putting it into a mortgage.

Personally, I’d include the opportunity cost of the mortgage, compare that to the opportunity cost of renting, and then see the difference in the years after the mortgage is paid off.

I haven’t done any calculations, but I believe that once the mortgage is paid off, the opportunity cost will change a bit because you now increased your net worth, you now have no rent for the rest of your life and that can go to investments. It is a bit hard to just compare only a mortgage without thinking of the cost of renting because we all need a place to live :).

Wonderful concept and one I plan to add to the toolbox when comparing things in the future – thank you!

Thanks for signing up, Chris! Although you won’t have to wait for the future iterations, as the 5-part series is already complete.

While this article represents #4 out of 5, You can find #5 in the series by using the “Next Post” link at the bottom of this article. For the sake of others reading this, you can also find the full series by locating the five articles titled “Compound Interest, Part X:” in the Archives:

https://www.thefinancialfreedomproject.com/the-archives/

You’re dead-on with the idea of comparing the opportunity costs of renting vs. buying. That should be a core calculation when first evaluating a home-shopping budget and when reviewing a specific loan amortization schedule.

Though as mentioned in the comments above, in the absence of a mortgage payment you’ll still need to account for ongoing home-ownership expenses in the form of property taxes, home insurance, and ongoing maintenance.

As a homeowner myself, I can attest to the fact that upkeep is no small part of the equation despite the fact that I’m an aspiring DIY’er and “insource” as many repairs as I can.

I can vouch for the fact no longer paying rent or a mortgage payment frees up a tremendous amount of money for investing or simply living a higher quality of life, whichever is your preference! It’s an incredible feeling.

I’m glad you found the article thought-provoking, and I’m glad to hear it may be of some use!

Great post. You did a nice job of breaking down the true cost of a mortgage and lost opportunity. It costs money to live in your own house or if you rent. Most people would not be able to ever buy a house if not for a mortgage. I don’t see any issue with taking out a mortgage if you truly want to own a house. Just take out a 15 year mortgage instead of a 30 and buy a smaller house than you can afford.

“buy a smaller house than you can afford.” – Truer words were never spoken, Dave!

Establishing a home shopping budget and calculating total interest owed over the life of a loan as well as the opportunity cost of that interest is critical to the home buying process.

My wife and I established our home shopping budget not from what the bank told us they’d be willing to lend us, but by reverse-engineering it from our ideal payoff timeline of approximately three years.

This was one of the best decisions we ever made, and it still pays dividends today. If you’re wondering why our goal was to be mortgage-free in three years, you can find more details at the below link:

https://www.thefinancialfreedomproject.com/financial-intentionality-the-9th-wonder-of-the-world/

I’m definitely not suggesting that people avoid taking out a mortgage, for the reasons you mentioned. For many (including my wife and I) it is/was the only way to afford home ownership.

But I’m a big believer in equipping folks to properly understand the true price tag of their mortgage as well as strategies they can take to avoid the wealth-killer of sustaining debt over the long term thanks to compound interest.

When my wife and I were shopping for our first home, I ran countless scenarios through loan amortization schedule calculators based on loan principal, various interest rates, and the effects of varying levels of extra payments.

I’m of the belief that everyone should do this prior to purchasing a home, as it is a great visual for exactly how powerfully compound interest can work against you.

In our case, doing so enabled us to develop a strategy for affording our home and avoiding major interest or opportunity cost penalties at the same time. Quadruple payments enabled us to put the mortgage to rest in just three years and two months, eliminating its ability to hamstring us over the long-term.

Great concept. You could even extend the opportunity cost figures on to retirement, because if you invested the money, you would likely keep it invested after the debt was paid.

In my book The Doctors Guide to Eliminating Debt, I did something similar. I compared the cost of paying the house off in 30 years vs 7 years. The extra interest means a doctor would have to see another 17,000 patients to pay for it. That is another opportunity cost.

Dr. Cory S. Fawcett

Prescription for Financial Success

Absolutely. Extending the time window makes the numbers even more staggering, thanks to giving compound interest even more time to work.

I used a $100,000 mortgage in this scenario because it’s a nice round number and easy to follow through the mortgage example, but also because I didn’t want to short-change readers with mortgages which are less than the 2017 American average of $211,500, according to data from the National Association of Realtors.

Just using the national average mortgage balance of $211,500 rather than the $100,000 example in the article puts the total opportunity cost at $802,164.66!

Just imagine what happens when the time horizon is increased from 30 years to all the way to retirement.

I love the concept of evaluating purchases in the context of work-hours or work-requirements. I use this approach often myself. Thanks for commenting! I’ll have to give your book a read.

If I wasn’t paying my $1200 mortgage id be paying $1900 in rent for a similar house so it saves us. We have zero debt other then our house. We’ve had out house for 1 year this month and have paid off 4 years of the mortgage no way am I handing them 150k in interest! Most people say don’t pay off the house early instead invest in the stock market but we are pretty safe and paying off our house is a garanteed return with a sense of accomplishment at the end.

Sounds like you have the right mentality and are on the fast track to paying off that house, Jen! There definitely is a train of thought that says invest rather than pay down a mortgage, but you’re right that the mortgage represents a “safer” investment due to the guaranteed rate of return.

One of the riskiest elements of using extra cash to invest in the stock market while you still have a mortgage is the fact that your cash flow requirements are still relatively high due to the mortgage debt. If you were to lose your job and be unable to replace your previous level of income to meet your bills, you run the risk of foreclosure and losing all equity in your home potentially without the ability to access the cash you had accrued in investments without fees and taxes taking a large chunk. There’s also the psychological factor, as you mentioned.

In some cases, you’ll even find that paying off the house first will trump the 7% historical rate of return of the stock market, even if the mortgage is only at 4-5% interest. There’s the cost of PMI to consider, and potentially other extenuating circumstances as well. This was the case for our situation, and I’m planning an upcoming post detailing the reasons why it was actually more advantageous for us to pay down the mortgage than to invest in the market.

Im trying to figure out what to do, save up money for 3 years and pay for a house in full or invest some of that money during that 3 years and have less money to put down on the house, but I will start earning compounding interest on my investment. What do you think?

The very fact that you’re weighing these two options and taking the time to read through online articles such as this one means your thought process is on the right track. I applaud you for crunching the numbers and being intentional with this decision. That’s half of the battle alone. Whichever route you elect to pursue, you’ll be much better off than someone who has blindly purchased a home without weighing the full impact of loan interest and opportunity cost.

Both courses of action have a wide array of advantages and disadvantages, but I’m afraid there is no single correct answer. On one hand, your thought process is correct inasmuch that the earlier you start investing and taking advantage of the power of compound interest to work in your favor, the more powerful the compound interest rocket to riches becomes.

I’ll add that it’s not just your investment returns after the three year period which you should consider when weighing this decision, but the returns of of the last three years of however long you expect your overall investment time horizon to be.

For example, the returns of a $10,000 investment in the stock market after three years may not be anything to write home about. But the returns of that same $10,000 investment over the final three year period of a 30-year time horizon will be much more substantial.

Technically it is the returns of the final three years of your investment time horizon which should be considered when weighing two alternative courses of action such as this, since the returns over those final three years will be impossible to achieve over a comparable 27-year time horizon in the above example.

And although houses are (usually) appreciating assets in their own right, they typically don’t increase in value at the same pace as does the stock market. For sake of reference, the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price NSA Index indicates that national housing prices have increased by 27.2% over the last 10 years, while the S&P 500 index indicates it has grown by 187.4% over that same span.

You also have the cyclical nature of the stock market to consider. In some situations the market may be overbought and prices artificially inflated. In others — such as the moment, after a nearly 20% correction — the market may be oversold and stocks available at a discount, representing an excellent buying opportunity.

The above points would appear to potentially favor using excess cash to invest rather than save to purchase a home outright, assuming we neglect the ancillary, non-financial benefits of homeownership. Now for the counter-points.

Using cash to purchase a home outright means you’ll be able to skip the loan origination fees which normally constitute the largest chunk of closing costs associated with a home purchase. A recent ValuePenguin study found that the closing costs on the national average home value of $198,000 would total $7,227, or 3.65%.

You’ll also avoid the need for Private Mortgage Insurance (PMI), a fee often charged on mortgages possessing home equity of less than 20%.

Rising mortgage interest rates over the near term pose another consideration. The average mortgage interest rates three years from now may well be higher than they are today, making purchasing a home with cash the more attractive option.

And don’t undervalue the fact that in a competitive housing market where current conditions favor the seller, an offer from a buyer which is not contingent on obtaining financing will likely be seen as more attractive. In a situation where you may be competing with multiple offers from other parties, a 100% cash transaction offers quicker turnaround time and a more guaranteed outcome. This may give you a leg up in your housing search.

There are a host of other factors playing into this decision which are too long to list here, including your current tax situation, the investment vehicles available to you, etc. Ultimately, only you will be able to weigh the pros and cons of each approach to determine which is best.

Hopefully this has given you some food for thought. But if you’d like to continue this conversation in more detail, I’d be more than happy to. You can reach me either by filling out the contact form here on the blog or by emailing me at MrFFP@TheFinancialFreedomProject.com. Best wishes!